41. A Lake Model of Employment#

41.1. Outline#

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

41.2. The Lake model#

This model is sometimes called the lake model because there are two pools of workers:

those who are currently employed.

those who are currently unemployed but are seeking employment.

The “flows” between the two lakes are as follows:

workers exit the labor market at rate

new workers enter the labor market at rate

employed workers separate from their jobs at rate

unemployed workers find jobs at rate

The graph below illustrates the lake model.

Fig. 41.1 An illustration of the lake model#

41.3. Dynamics#

Let

The total population of workers is

The number of unemployed and employed workers thus evolves according to:

We can arrange (41.1) as a linear system of equations in matrix form

Suppose at

Then,

Thus the long-run outcomes of this system may depend on the initial condition

We are interested in how

What long-run unemployment rate and employment rate should we expect?

Do long-run outcomes depend on the initial values

41.3.1. Visualising the long-run outcomes#

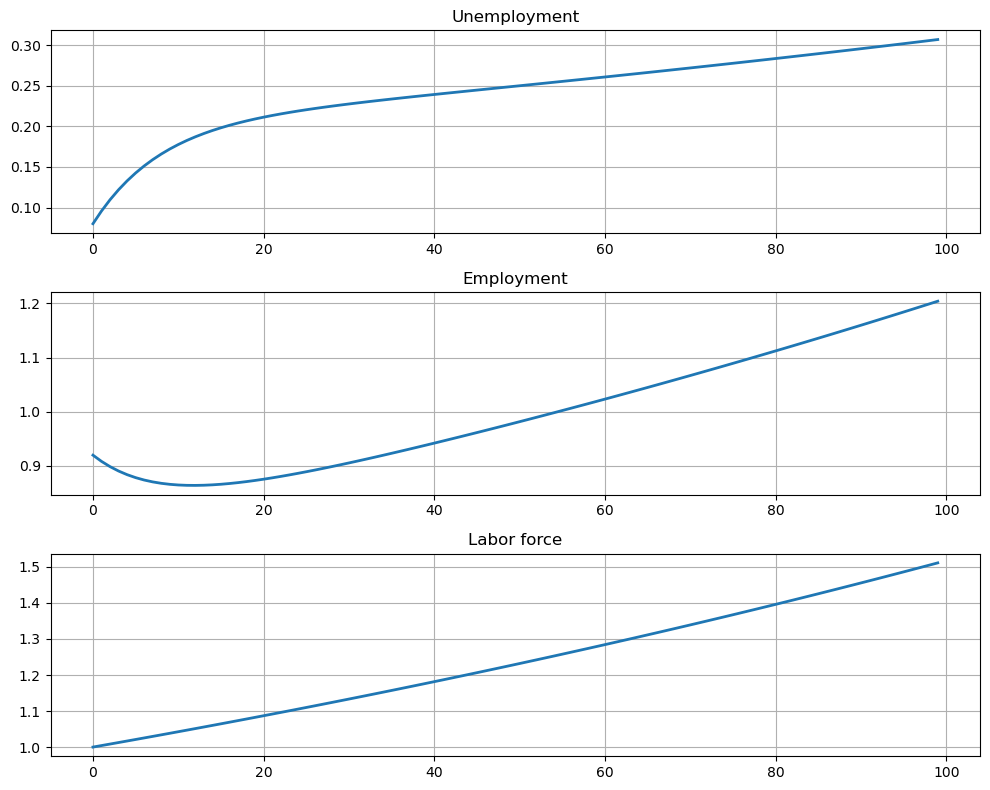

Let us first plot the time series of unemployment

class LakeModel:

"""

Solves the lake model and computes dynamics of the unemployment stocks and

rates.

Parameters:

------------

λ : scalar

The job finding rate for currently unemployed workers

α : scalar

The dismissal rate for currently employed workers

b : scalar

Entry rate into the labor force

d : scalar

Exit rate from the labor force

"""

def __init__(self, λ=0.1, α=0.013, b=0.0124, d=0.00822):

self.λ, self.α, self.b, self.d = λ, α, b, d

λ, α, b, d = self.λ, self.α, self.b, self.d

self.g = b - d

g = self.g

self.A = np.array([[(1-d)*(1-λ) + b, α*(1-d) + b],

[ (1-d)*λ, (1-α)*(1-d)]])

self.ū = (1 + g - (1 - d) * (1 - α)) / (1 + g - (1 - d) * (1 - α) + (1 - d) * λ)

self.ē = 1 - self.ū

def simulate_path(self, x0, T=1000):

"""

Simulates the sequence of employment and unemployment

Parameters

----------

x0 : array

Contains initial values (u0,e0)

T : int

Number of periods to simulate

Returns

----------

x : iterator

Contains sequence of employment and unemployment rates

"""

x0 = np.atleast_1d(x0) # Recast as array just in case

x_ts= np.zeros((2, T))

x_ts[:, 0] = x0

for t in range(1, T):

x_ts[:, t] = self.A @ x_ts[:, t-1]

return x_ts

lm = LakeModel()

e_0 = 0.92 # Initial employment

u_0 = 1 - e_0 # Initial unemployment, given initial n_0 = 1

lm = LakeModel()

T = 100 # Simulation length

x_0 = (u_0, e_0)

x_path = lm.simulate_path(x_0, T)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(3, 1, figsize=(10, 8))

axes[0].plot(x_path[0, :], lw=2)

axes[0].set_title('Unemployment')

axes[1].plot(x_path[1, :], lw=2)

axes[1].set_title('Employment')

axes[2].plot(x_path.sum(0), lw=2)

axes[2].set_title('Labor force')

for ax in axes:

ax.grid()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Not surprisingly, we observe that labor force

This coincides with the fact there is only one inflow source (new entrants pool) to unemployment and employment pools.

The inflow and outflow of labor market system is determined by constant exit rate and entry rate of labor market in the long run.

In detail, let

Observe that

Hence, the growth rate of

Moreover, the times series of unemployment and employment seems to grow at some stable rates in the long run.

41.3.2. The application of Perron-Frobenius theorem#

Since by intuition if we consider unemployment pool and employment pool as a closed system, the growth should be similar to the labor force.

We next ask whether the long-run growth rates of

The answer will be clearer if we appeal to Perron-Frobenius theorem.

The importance of the Perron-Frobenius theorem stems from the fact that firstly in the real world most matrices we encounter are nonnegative matrices.

Secondly, many important models are simply linear iterative models that

begin with an initial condition

This theorem helps characterise the dominant eigenvalue

41.3.2.1. Dominant eigenvector#

We now illustrate the power of the Perron-Frobenius theorem by showing how it helps us to analyze the lake model.

Since

the spectral radius

any other eigenvalue

there exist unique and everywhere positive right eigenvector

if further

The last statement implies that the magnitude of

Therefore, the magnitude

Recall that the spectral radius is bounded by column sums: for

Note that

Denote

The Perron-Frobenius implies that there is a unique positive eigenvector

Since

This dominant eigenvector plays an important role in determining long-run outcomes as illustrated below.

def plot_time_paths(lm, x0=None, T=1000, ax=None):

"""

Plots the simulated time series.

Parameters

----------

lm : class

Lake Model

x0 : array

Contains some different initial values.

T : int

Number of periods to simulate

"""

if x0 is None:

x0 = np.array([[5.0, 0.1]])

ū, ē = lm.ū, lm.ē

x0 = np.atleast_2d(x0)

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 8))

# Plot line D

s = 10

ax.plot([0, s * ū], [0, s * ē], "k--", lw=1, label='set $D$')

# Set the axes through the origin

for spine in ["left", "bottom"]:

ax.spines[spine].set_position("zero")

for spine in ["right", "top"]:

ax.spines[spine].set_color("none")

ax.set_xlim(-2, 6)

ax.set_ylim(-2, 6)

ax.set_xlabel("unemployed workforce")

ax.set_ylabel("employed workforce")

ax.set_xticks((0, 6))

ax.set_yticks((0, 6))

# Plot time series

for x in x0:

x_ts = lm.simulate_path(x0=x)

ax.scatter(x_ts[0, :], x_ts[1, :], s=4,)

u0, e0 = x

ax.plot([u0], [e0], "ko", ms=2, alpha=0.6)

ax.annotate(f'$x_0 = ({u0},{e0})$',

xy=(u0, e0),

xycoords="data",

xytext=(0, 20),

textcoords="offset points",

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle = "->"))

ax.plot([ū], [ē], "ko", ms=4, alpha=0.6)

ax.annotate(r'$\bar{x}$',

xy=(ū, ē),

xycoords="data",

xytext=(20, -20),

textcoords="offset points",

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle = "->"))

if ax is None:

plt.show()

lm = LakeModel(α=0.01, λ=0.1, d=0.02, b=0.025)

x0 = ((5.0, 0.1), (0.1, 4.0), (2.0, 1.0))

plot_time_paths(lm, x0=x0)

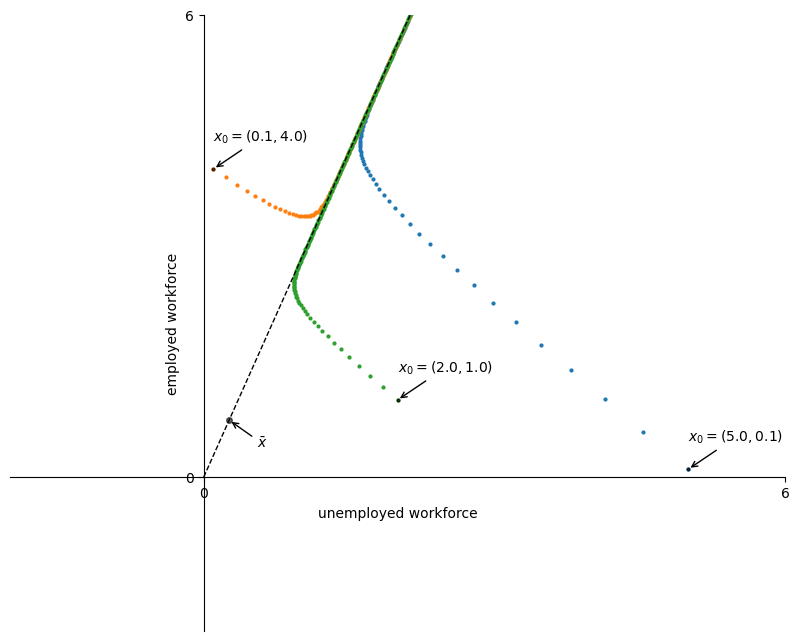

Since

This set

The graph illustrates that for two distinct initial conditions

This suggests that all such sequences share strong similarities in the long run, determined by the dominant eigenvector

41.3.2.2. Negative growth rate#

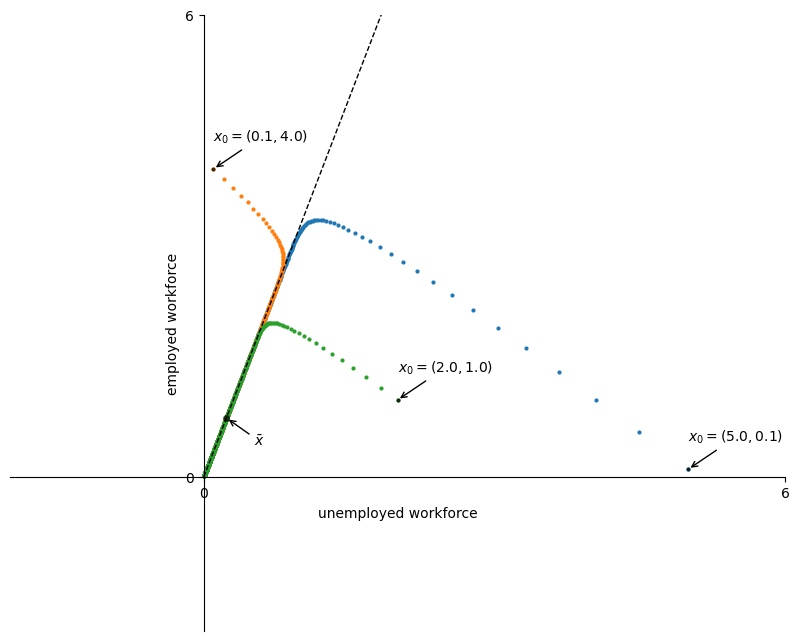

In the example illustrated above we considered parameters such that overall growth rate of the labor force

Suppose now we are faced with a situation where the

This means that

What would the behavior of the iterative sequence

This is visualised below.

Thus, while the sequence of iterates still moves towards the dominant eigenvector

This is a result of the fact that

This leads us to the next result.

41.3.3. Properties#

Since the column sums of

Perron-Frobenius theory implies that

As a result, for any

as

We see that the growth of

Moreover, the long-run unemployment and employment are steady fractions of

The latter implies that

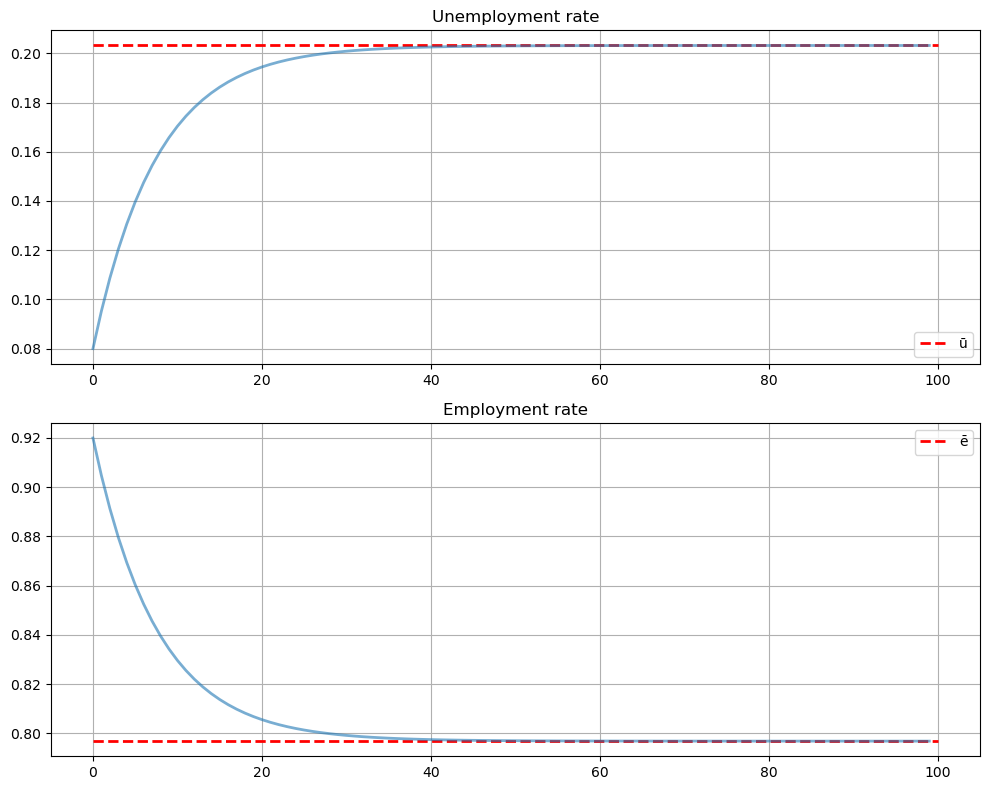

In detail, we have the unemployment rates and employment rates:

To illustrate the dynamics of the rates, let

The dynamics of the rates follow

Observe that the column sums of

One can check that

Moreover,

This is illustrated below.

lm = LakeModel()

e_0 = 0.92 # Initial employment

u_0 = 1 - e_0 # Initial unemployment, given initial n_0 = 1

lm = LakeModel()

T = 100 # Simulation length

x_0 = (u_0, e_0)

x_path = lm.simulate_path(x_0, T)

rate_path = x_path / x_path.sum(0)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(10, 8))

# Plot steady ū and ē

axes[0].hlines(lm.ū, 0, T, 'r', '--', lw=2, label='ū')

axes[1].hlines(lm.ē, 0, T, 'r', '--', lw=2, label='ē')

titles = ['Unemployment rate', 'Employment rate']

locations = ['lower right', 'upper right']

# Plot unemployment rate and employment rate

for i, ax in enumerate(axes):

ax.plot(rate_path[i, :], lw=2, alpha=0.6)

ax.set_title(titles[i])

ax.grid()

ax.legend(loc=locations[i])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

To provide more intuition for convergence, we further explain the convergence below without the Perron-Frobenius theorem.

Suppose that

Let

The dynamics of the rates follow

Consider

Then, we have

Hence, we obtain

Since

Therefore, the convergence follows

Since the column sums of

In this case,

41.4. Exercise#

Exercise 41.1 (Evolution of unemployment and employment rate)

How do the long-run unemployment rate and employment rate evolve if there is an increase in the separation rate

Is the result compatible with your intuition?

Plot the graph to illustrate how the line

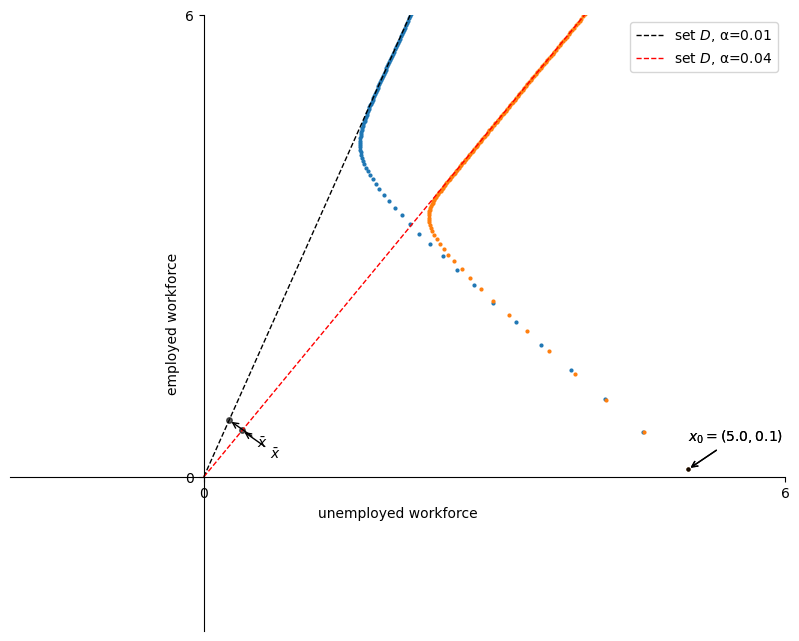

Solution to Exercise 41.1 (Evolution of unemployment and employment rate)

Eq. (41.3) implies that the long-run unemployment rate will increase, and the employment rate will decrease

if

Suppose first that

The below graph illustrates that the line

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 8))

lm = LakeModel(α=0.01, λ=0.1, d=0.02, b=0.025)

plot_time_paths(lm, ax=ax)

s=10

ax.plot([0, s * lm.ū], [0, s * lm.ē], "k--", lw=1, label='set $D$, α=0.01')

lm = LakeModel(α=0.04, λ=0.1, d=0.02, b=0.025)

plot_time_paths(lm, ax=ax)

ax.plot([0, s * lm.ū], [0, s * lm.ē], "r--", lw=1, label='set $D$, α=0.04')

ax.legend(loc='best')

plt.show()